News and Events

The Thabo Mbeki Letters, Part 1: Intellectual Traditions

In “Thabo Mbeki and African Intellectual Traditions: A Brief Note” by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu and Maanda Ndhlovu, the political life of one of the iconic political leaders of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, is examined. Mbeki is an unparalleled intellectual giant in South Africa and a statesman of global stature. His ideas opened the way for his political career and the question of African identity, post-colonialism, and African intellectual traditions. His thoughts and ideas are founded on African history and cultural heritage, which is the basis for his intellectual framework: an incorporation of traditional African thoughts with modern political theory.

Thabo Mbeki Former President of South Africa

It is impossible to understand Mbeki’s intellectual development and trajectory without reference to how the authors explain how Mbeki’s intellectual project in the post-1994 era was an attempt to reclaim the glorious African past through the call for an African renaissance and affirmation of African identity, a call that identifies with certain universal claims of modern Western humanism, those of justice, peace, equality, as well as democracy. They further stated that Mbeki’s intellectual compass embraces a rich heritage of political ideas that resonate with the black intellectual tradition of the nineteenth century’s New African Movement in South Africa, as defined by Ntongela Mesilela in his research on this subject.

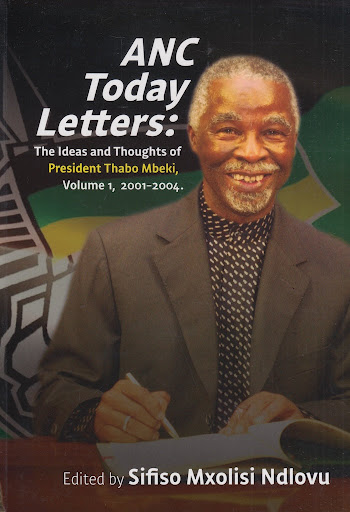

A large part of Chapter One in ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004 discusses how Mbeki is portrayed as a direct successor of the New African Movement, which, according to the editors of the volume, was a period in history that was marked by the rise of a new generation of African intellectuals who sought to contextualise colonial oppression, and the fight for independence to redefine African identity. This is evident, as suggested by the editors, in Mbeki’s advocacy of the African Renaissance during his presidency, which is a continuation of the objectives of the “New African Intellectuals.”

Worthy of note is Mbeki’s belief in the transformative power of knowledge, which is reflected in his advocacy for education and intellectual development as tools for empowerment, highlighting the establishment of African institutions of higher learning which will produce forward-thinking problem solvers. It is also commendable that the editors did not refrain from addressing the challenges and criticism that was a part of Mbeki’s political career, particularly his controversial stance on HIV/AIDS. Not a few public health problems arose in South Africa because of his scepticism about the connection between HIV and AIDS. The editors critically analyse this significant period in Mbeki’s political trajectory, looking at how his intellectual approach may have influenced his decision-making at the period and how this approach birthed countless problems and controversies for him. This points to the fact that intellectualism is not a sufficient criterion for good leadership.

ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004, Book Cover

The collection of letters strives to contextualise Mbeki’s intellectual thoughts and practice within the black intellectual tradition, stating that intellectual work differs from academic because one does not need to undertake a formal course of study or strive for degrees to live the life of the mind.

In South Africa, African intellectuals are categorised into three types: Old African Intellectuals, New African Intellectuals, and Radical African intellectuals. Mbeki’s representation of these three African intellectual traditions is pointed out. Using Toyin Falola’s work, Nationalism and African Intellectuals, Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu and Maanda Ndhlovu explain the “Old African Intellectuals,” which Falola termed as ‘traditional intellectuals /traditional elites’, who had no formal education, developed the means of creating and transmitting their cultures from one generation to the next. It is from Falola that the editors delved into how Mbeki’s link to the old African intellectual tradition. Mbeki is a public intellectual who displays his love for poetry openly, in whatever form, whether in its African or European/Western variety. Pointing out Mbeki’s representation by both Malogwane ka Mkhatini Jiyane and Mshongweni, which are two of the finest pre-colonial Izimbongi originating from south-eastern Africa. Demonstrating his strength and resilience, Mbeki used an older voice to publicly criticise members of the government, the liberation movement, and the ruling party who abused power and leadership positions.

Mbeki’s poetic voice connects to both Magoliane and Mshongweni as public intellectuals who utilised Izibongo to articulate public history. The editors deploy the term “public intellectuals” in its widest sense to include people who did not necessarily receive any formal education in mission schools or any other formal educational establishments.

Professor Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu

Additionally, Mbeki’s involvement in elaborate historiographical contestation with colonisers and imperialists and those who believe in scientific racism and Social Darwinism qualifies him to be classified as a public intellectual, one who ponders on the meaning and significance of social and public life, philosophy, religion, history, literature, politics, and culture. Mbeki used poets and poetry to elaborate his thoughts and ideas. This was seen in how he invoked the two poems written by Berthold Brecht “to pay respect and homage to the deceased Palestinian leader and hero, Yasser Arafat.”

The second category of African intellectuals, known as the “New African Intellectuals,” is comprised of individuals who were educated in the Western education system or at missionary schools in Southern Africa run by Western-based missionary societies. The book provides insight into how Tiyo Soga, who was the first Western-educated African intellectual in the history of the “New African Intellectuals,” was deeply engaged in the quest to forge and construct African modernity parallel to that of European modernity. The authors highlight the crisis of the “New African Intellectuals” and its failures and commend their efforts in propagating African modernity and the founding of the ANC. The author describes Mbeki’s examination of South Africa’s modern economy as important in that the advent triggered the emergence of black South African Intellectual tradition in response to Western modernity. Mbeki displayed profound empathy and deep respect for the “New African Intellectuals.”

Thabo Mbeki Former President of South Africa and Professor Toyin Falola

The “Radical African Intellectuals” and the “New African Movement,” being the third group, took control of the mother body, the ANC, through its emergence in the youth league and revolutionised the organisation to meet the challenges of the 1950s and beyond. The “Radical African Intellectuals” and the “New African Movement” were the generation that took it upon themselves to re-imagine the ANC’s conservative ideology into a new ideology of African Nationalism. During the emergence of this group, an ideological shift occurred within the ANC from conservatism to progressivism, which would redefine the New African Movement and the political history of South African politics and black intellectual tradition.

The editors describe Mbeki as an ardent proponent of black intellectual tradition and the “New Africanism,” which is why his ideology of Africanism finds expression in his political leadership, speeches, policies, and programs, both for South Africa and the entire African continent. Mbeki believes that the New African represents the past and present as they unfold into the future of South Africa.

Prof. Toyin Falola at the Thabo Mbeki African School of Public and International Affairs, UNISA

The book gives a detailed highlight of Thabo Mbeki’s ANC Letters reflected in the struggles for freedom, nation-building and reconciliation, economic justice, poverty eradication and development, Culture, Education, Politics, Internal Dynamics and Corruption, Internationalism, Human Solidarity, Peace, Diplomacy and conflict Resolution.

This is a 12-part series based on the collections edited by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, titled ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004, supplemented by materials in the Thabo Mbeki Museum, UNISA, Pretoria. The series is composed over five weeks in three different countries.

For the original article, visit: The Thabo Mbeki Letters, Part 1: Intellectual Traditions - Toyin Falola Network

Publish date: 2024-09-02 00:00:00.0

Unisa explores strategic education collaboration in the North West Province

Unisa explores strategic education collaboration in the North West Province

Orange Day against GBVF: A community stands united

Orange Day against GBVF: A community stands united

Unisa, EC industry leaders discuss collaboration to enhance catalytic niche areas

Unisa, EC industry leaders discuss collaboration to enhance catalytic niche areas

Black industrialist and founding CEO of Capebio to deliver keynote address at Innovation Festival

Black industrialist and founding CEO of Capebio to deliver keynote address at Innovation Festival

Unisa connects with Giyani community to define tomorrow

Unisa connects with Giyani community to define tomorrow